News item | 07-12-2016

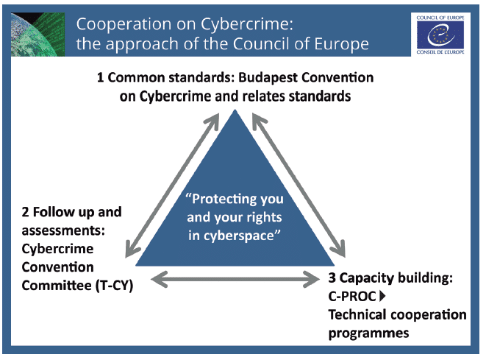

The Convention on Cybercrime of the Council of Europe was opened for signature in Budapest in November 2001. Fifteen years later, it remains the most relevant international agreement on cybercrime and electronic evidence. Membership keeps growing, while both the quality of implementation and the level of cooperation between Parties keep improving, and the treaty itself is evolving to meet new challenges. The formula for success is a “dynamic triangle”; The Budapest Convention is complemented by an effective follow up mechanism and by capacity building programmes, which are fed back into the Committee, contributing towards the Convention’s evolution. The leitmotif of this approach is “to protect you and your rights in cyberspace”.

Written by: Alexander Seger, Executive Secretary of the Cybercrime Convention Committee and Head of the Cybercrime Division at the Council of Europe in Strasbourg, France.

Building on agreement

Cybercrime has been around for more than 40 years. The Council of Europe had been dealing with this topic from a criminal law perspective from the mid-1980s onwards. By 2001, the issue had become sufficiently important to warrant a binding international treaty. Negotiated by the member States of the Council of Europe together with Canada, Japan, South Africa and the United States of America, the Convention on Cybercrime was opened for signature in Budapest, Hungary, in November 2001.

Since then, information and communication technologies (ICT) have transformed societies worldwide. They have also made them highly vulnerable to security risks such as cybercrime.

While there is recognition of the need to strengthen security, confidence and trust in ICT and to reinforce the rule of law and the protection of human rights in cyberspace, all things “cyber” have now become too important. As they touch upon fundamental rights of individuals as well as national (security) interests of States, it is increasingly difficult to reach international consensus on common solutions.

In order to overcome this dilemma, the most sensible approach is to focus on common standards that are already in place and functioning, such as the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime, and on approaches on which there is broad agreement, in particular, capacity building.

Cybercrime Convention Committe (T-CY), Plenary session, May 2016. Credits: Council of Europe.

Common standards: the Budapest Convention

The Budapest Convention is a criminal justice treaty that provides States with (i) the criminalisation of a list of attacks against and by means of computers; (ii) procedural law tools to make the investigation of cybercrime and the securing of electronic evidence in relation to any crime more effective and subject to rule of law safeguards; and (iii) international police and judicial cooperation on cybercrime and e-evidence.

It is open for accession by any State prepared to implement it and engage in cooperation. By November 2016, which marked also the 15th anniversary of the Convention, 50 States were Parties (European countries as well as Australia, Canada, Dominican Republic, Israel, Japan, Mauritius, Panama, Sri Lanka and the USA). Another 17 from all regions of the world had signed it or been invited to accede.

Assessments and follow up: Cybercrime Convention Committee

These States that currently amount to 67, together with ten international organisations (such as the Commonwealth Secretariat, European Union, INTERPOL, the International Telecommunication Union, the Organisation of American States, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime and others), participate as members or observers in the Cybercrime Convention Committee. This Committee assesses implementation of the Convention by the Parties, and keeps the Convention up-to-date. Current efforts focus on solutions regarding law enforcement access to electronic evidence on cloud servers.

Capacity building

The value of capacity building in relation to cybercrime and -security is not a new discovery. International calls for technical assistance to reinforce criminal justice capacities on cybercrime have been made for decades. Following adoption of the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime in 2001, the Council of Europe began to assist countries in the implementation of this treaty, first within Europe and from 2006 also in other regions of the world, often in cooperation with the European Union.

However, the year 2013 brought the matter to yet another level. The need for a broad agreement on capacity building was stated in February 2013 by the United Nations Intergovernmental Expert Group on Cybercrime and by the European Union in its Cybersecurity Strategy.

In October 2013, it was the focus of the Global Cyber Space Conference in Seoul, Korea. Building on this momentum, the the European Union and the Council of Europe followed by up immediately and in the very same week signed their agreement on the joint project on ‘Global Action on Cybercrime’ (GLACY), while at the same time, the Council of Europe decided to establish a Cybercrime Programme Office (C-PROC) for worldwide capacity building in Bucharest, Romania.

The creation – at the subsequent Global Cyber Space Conference (Netherlands, April 2015) – of the Global Forum on Cyber Expertise was a further logical consequence.

By August 2016, C-PROC managed a series of projects – including several joint projects with the European Union – covering the Eastern Partnership region (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine) or South-Eastern Europe and Turkey (the project ‘iPROCEEDS’ is targeting proceeds from crime online).

With a broader geographical scope, the ‘Global Action on Cybercrime’ project (GLACY) assists Mauritius, Morocco, Philippines, Senegal, South Africa, Sri Lanka and Tonga. These are priority countries given their political commitment to implement the Budapest Convention. With GLACY ending in October 2016, several of these countries will be able to share their experience within their respective regions by serving as hubs under the new joint EU-CoE project ‘Global Action on Cybercrime Extended’ (GLACY+), which runs from 2016 to 2020.

Conclusion

Experience in recent years has shown that capacity building indeed is an effective way to help societies meet the challenge of cybercrime.

In general terms, political commitment, reference to common international standards and continuous participation in international peer reviews enhance the chances of success of capacity building programmes. Each project or organisation may have its own formula to make this work.

For the Council of Europe, the Budapest Convention, the Cybercrime Convention Committee and capacity building by C-PROC form a “dynamic triangle”: Capacity building programmes support the implementation of the Budapest Convention as well as recommendations of the Cybercrime Convention Committee; and at the same time, the experience of capacity building programmes is fed back into the Committee and the further evolution of the Convention. The long-term involvement of “project countries” in the Cybercrime Convention Committee helps sustain the process beyond the life cycle of individual projects.

This article first appeared in the second issue of the Global Cyber Expertise Magazine – November 2016.